A tale of two bars in 2016:

It’s the Saturday night of the Millennium journal’s conference on race and racism in International Relations, and four of us from our panel on race, Yugoslavia, India and Non-Alignment have walked up the back ways of Holborn in the October night looking for a place where we can sit and drink; a cramped, semi-underground Indo-Chinese cocktail bar has its back door open (I later found out it was called ‘Bollywood Stories’), and we settle around a small cellar table under the stairs, Srđan, Jelena, Aida and I, one candle flickering between us, contemplating what we don’t have to say out loud about the vote there’s just been in this country and the vote there’s about to be in the USA, and where what we know about what we don’t have to say comes from;

Four months earlier, it’s the day after that referendum, I’ve been away in Newcastle at a feminist international relations conference, up till 4.30 am until I couldn’t take any more of Nigel Farage grinning about bullets ten days after a white nationalist had shot Jo Cox dead in the middle of the street, and the group of us from my department who sometimes go for a drink after work have mutually agreed we need one tonight. We’re all white men and women from various parts of England, two from Hull, one from Derbyshire, me from the South (or maybe there are five of us, and our colleague who’s Australian is there as well); and soon after I’ve dropped my bag at home and found them in the large back room of one of the pubs near work, we’ve got on to constitutional implications, and I’ve said ‘Scotland’s gone’ without missing a beat; and someone or everyone says ‘Really?!’ because my consciousness has made a leap theirs hasn’t yet. (A few days later I think through all the resonances of constitutional fragmentation and ethnicised polarisation from the break-up of Yugoslavia that the atmosphere before and after the referendum is evoking, in an essay for LSE’s European Politics and Policy blog that comes out in one sitting about fourteen hours long: it comes to about 7,000 words.)

The astonishingly wise, frank, raw, and honest series of daily blog posts that Aida, Jelena and Srđan have edited all month at The Disorder of Things calls a foreknowledge based on living through the disintegration and destruction of Yugoslavia ‘Yugosplaining’:

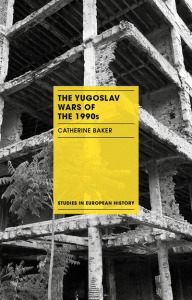

At the time, the Yugoslav wars and their extreme violence were viewed by the West as idiosyncratic, isolated events, unrelated to broader process of political and economic transformation in the world – the end of the Cold War, the collapse of the Soviet Union, the end of communism. Indeed, they were just outright inconvenient for the world that celebrated the end of history. Yugoslavia, once deeply entangled with both the East and the West and even more so with the Global South, was all of a sudden isolated from history – including its own.

Yet now, as the West (and the allegedly democratized East) unravel under the weight of their own unresolved histories – and not just of the successive lost wars, financial crises or the pandemics – it seems that the ghosts of the 1990s are back to haunt us. Nationalism, ethnic and racial violence, populism, militias, lies and conspiracies can no longer be viewed as “the Balkan” phenomena. Instead, “the Balkans” now appears as the vanguard of a common catastrophe (Subotić, Hemon).

Concluding the series, they wrote yesterday:

The aim was twofold: first, to use the authors’ lived personal experience of Yugoslavia as a way of explaining our lived political experience elsewhere. Second, to reclaim the narrative of our own lives rather than be made subject to outsiders’ accounts.

Decades after its demise, Yugoslavia continues to act as an open wound. We live what Saida Hodžić wrote in her essay – “if home is a wound that splits open the world, the world neither stays open nor heals over.” Therefore, this series was not designed to explain what Yugoslavia was, what it meant to whom, who it included or excluded, or how it came apart or why. It was, instead, designed to explain our current moment – that world split open – through the experience of our past.

These are knowledges that, working in the Western academy, the contributors have seen painfully silenced again and again by Western presumptions about what happened in ‘the Balkans’ and what ‘the Balkans’ must have been like for it to happen there, as Aida, Azra Hromadžić and Saida Hodžić all painfully record.

I felt none of Yugoslavia’s break-up on my body. My experiences of the wars were mediatised backdrops to everyday pre-teen routine, as a racial- and ethnic-majority subject of a nation that was setting itself up as a humanitarian donor, diplomatic negotiator and conditional peacekeeper (which measured its contributions by the risk to British, not Bosnian, lives): a newsreader on my mother’s radio in the kitchen saying tanks had crossed the Slovenian border; the War Child appeal and ‘Miss Sarajevo’ on Top of the Pops; an Evening Standard headline about Srebrenica at the station, and footage of disarmed Dutch soldiers on the six o’clock news by the time I came home from school.

And yet the ways I’ve tried to understand how the wars became possible and what they did to everyday life have done something to my subjectivity, to the deep premises I know about how societies and international politics work, about how people come to see others as enemies, and the myths they tell about the future and the past.

As a PhD student, I wanted to understand how a music industry like Croatia’s could have separated itself from Yugoslavia so quickly, and how it had been part of transforming everyday public consciousness in the ways that the Croatian anthropologists and ethnomusicologists I’d started reading during my Masters had documented at the very beginning of the war. Stitching together the Croatian war of independence and its aftermath, day by day, over one long spring and two long summers in Croatia’s national library (year by year in reverse, so 1990 came last every time, and then it was back to the then-present with another newspaper or showbusiness magazine), the slippage of political deadlock into armed clashes into something ever worse was not the sudden blaze of Western book covers and documentary title screens; how would I know if this were only a few months away?

More of what I know about living through those years comes from deep listening. In my postdoctoral work, I interviewed thirty-odd Bosnians and other ex-Yugoslavs about the work they’d done as interpreters and translators for foreign peacekeeping forces in Bosnia-Herzegovina, during and after the war. Some would have been direct contemporaries of Danijela Majstorović, who wrote about her own and her research participants’ migration in another of the Yugosplaining essays; we somehow missed each other during my research visits (we’re still not sure how). I must have been in Priština, where I’d gone to interview a former British military linguist for another strand of the project, just as former Bosnian interpreters were responding to a post I’d made in a Facebook reunion group about setting up interviews later in the year, when I was coming back from meeting an ex-KFOR interpreter someone had connected me to and the thought came to me: many of the people I’d been meeting had been languages students or languages graduates when the war came; so were most of my friends at the time; if something like this had happened where we lived [in a completely different global configuration of languages, statehood and power, of course; but that only came later], is this what we’d have done?

These are acts of imagination, just as everything I know about the region that used to be Yugoslavia is in some way a construction. It only sits inside my mind through scholarship; it does not sit in my bones. What do sit in my bones are the experiences and sensations of the scholarship itself – the work, the research, the presentations, the listening, the conversations, and all the imaginative backchannels that run while my frontstage does those things. Among the authors are friends, contemporaries, authorities, table-of-contents mates and tablemates, people to whom I strive to make my representations of Yugoslavia and its aftermath authentic and accountable, to whom I owe a responsibility to depict as much complexity as they can see.

In essays such as the piece by Dženeta Karabegović, Slađana Lazić, Vjosa Musliu, Julija Sardelić, Elena B Stavrevska and Jelena Obradović-Wochnik, writing as the Yugoslawomen+ Collective and using their own experiences as knowledge-producers and subjects who have waited to cross borders to think through how rhetoric about ‘desirable’ and ‘undesirable’ migrants has changed since the 1990s, I hear echoes of dialogues that I’ve joined in as well in conference corridors and email exchanges, working through this last decade’s reckoning with racism and the global legacies of colonialism from where we each are:

The post-Yugoslav space from which people once fled, and from which they still continue to migrate, is now also known as a ‘transit’ zone for those fleeing ongoing violence elsewhere. The region once known for ‘the Yugoslav wars’ is now ‘the Balkan Route’, the EU’s imagined ‘Badlands’, the outer periphery where border security funds are channelled to prevent the onward migration of racialised ‘others.’ The so-called ‘Balkan route’ became an alternative once the sea crossings were deemed too dangerous; today, it has become so entrenched in the violence of EU’s border-keeping that just one monitoring group in the region has recorded more than 700 reports of police brutality and asylum denials, with 70% of incidents reportedly taking place in Croatia.

Countries of the former Yugoslavia, most notably Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia, whose ‘good migrants’ have often managed to leave the region and arrive in relative safety to countries of the Global North, are now implicated in the EU’s border-keeping to the extent that they regularly participate in the violent ‘push backs’ of men, women and children from the EU’s external border. Their aspirations to ‘Europeanness’, understood primarily as EU membership, are exercised through the protection and legitimization of the European superiority, even though their own citizens’ mobility within the EU is limited. […] The region is, thus, simultaneously othered and implicated in further othering in migration discourses. These racialised and classed hierarchies of people on the move are perpetuated, despite thousands of people from the post-Yugoslav space continuously lining up in front of EU and other Global North countries’ embassies or looking for ways to get EU citizenship so they can migrate more easily.

Something has, or somethings have, committed all of us to perceiving Yugoslavia and the violence of its collapse, and the systemic violence emanating in all its global forms from Europeans’ enslavement of Africans and colonisation of Indigenous lands, as part of the same world.

(The very question of who feels able to write themselves into a ‘Yugoslav’ past is shaped by such power relations, as Vjosa noted at the beginning of the series when explaining why she had participated in it as an ethnic Albanian from Kosovo, and as Jelena, Srđan and Aida acknowledged in their conclusion: almost all its contributors came from South Slav backgrounds, and Yugoslavia’s failure to confront ‘the longer history of anti-Albanian bigotry’ in the region undercut its aspirations to ‘brotherhood and unity’ even before we weigh up how well it balanced the rights and interests of different South Slavs.)

Later in Azra’s essay, she writes of discussing her wartime experiences of being labelled as a Bosnian Muslim with inner-city Philadelphia schools, and trying to comfort disoriented students on her ‘Peace and Conflict in the Balkans’ class immediately after Trump’s election, as ‘openings’ that defy the ‘closings’ that have pressed on her in prestigious academic spaces: these openings are ‘transactions in sociopolitical life when “structures of feeling” were somehow transmitted and felt, almost understood, across the sociopolitical, geographic, and historical spectrum’. My own knowledge and I are the outcomes of many such openings, and are measured by them as well.

Three weeks after Srđan, Aida, Jelena and I sat together in Holborn, the US election result came in: overnight for them, first thing in the morning for me. Whatever else I’d been meant to do that day, the only thing I could do was write, a messy 3,000 words on coming to terms with how quickly queer people’s newborn rights could be taken away overnight, and why the result filled me as a queer woman with dread even an ocean away. (I re-used part of it when Cai Wilkinson was editing a special section of Critical Studies on Security and invited me to rework it as an essay I ended up calling ‘The filter is so much more fragile when you are queer’.

(One line I added to the piece for Cai has kept coming back into my head, this pandemic year: ‘There are people I know or used to know who will be dead in four years’ time.’)

My consciousness of my own nation and its past would not be what it is without learning about post-Yugoslavia for so long. Jelena (Subotić) writes, in her essay on citizens’ moral implication in the violence of Milošević’s Serbia or Trump’s USA, of our ‘larger, metaphysical responsibility as citizens who still benefit from structural racism or from structural inequality, or from structural anti-immigration policies. Even if we oppose them, by our own position in society we are implicated in them – an argument that goes at least as far back as Karl Jaspers’. To hope for a transparent reckoning with the past in Croatia or Serbia (I’d understood by the end of my PhD), it would be a double standard not to work towards the same in Britain – a country whose imperial and slave-trading past had systemic consequences around the world.

Knowing about post-Yugoslavia through the ‘openings’ I’d been part of for years, I suggested at the end of the queer in/security pieces, had made me more able to understand that Britain was not immune to the kind of authoritarian, nationalist future that now seemed to be coming to pass:

I know without having lived it that ethnopolitical conflict works like that.

The anxieties over ‘dilution’ or ‘undermining’ national cultural values that racists and xenophobes intensify in order to mobilise public support for restricting immigration work like that.

[…] Studying the Yugoslav wars since my early twenties, when all that preoccupied me at the time they were happening was making sense of the confusion with which I entered my own queer teens: I know identities wax strongest, turn from individual to collective, description to politics, when people believe or are led to believe that that identity is why they’re under threat.

I know it through compressing acres of wartime newsprint into weeks of research, through collecting hours upon hours of memories, through years of friendship and listening and solidarity, all breaking down my own filter of it-can’t-happen-here.

But I’d also suggested that having grown up queer, knowing that my belonging to the respectable majority would only ever be conditional, had made that filter more fragile and perhaps helped me to feel the solidarities I do:

There are freedoms I have in England or would have in America, which I didn’t even expect to enjoy as a teenager but which my queer elders won for me. In doing so, I gained a strange kind of everyday security with an uncanny contingency underneath – which I could lose again in ways that, if they were proposed for straight people, would be the stuff of dystopia, ‘some Handmaid’s Tale shit right there’.

(Dystopia still happens. But it takes so many more guns.)

Did knowing these kinds of insecurity with my own body make me more detachable from the idea that the territory–nation–culture nexus I was born in should automatically be a place of safety, progress and inspiration to the rest of the world – an idea that has so readily slipped into many Westerners’ belief that their knowledge is the most authoritative on ‘Balkan affairs’? I am wary of saying that queerness alone is enough to create an alliance – and yet if anything in my life has predisposed me to step away from the Anglophone West being at the centre of the world, that must be what it must be. (Did failing to fit the norms of heterosexual and class success at a school that was supposed to train girls to join Britain’s institutions of power do that?)

Without directly experiencing the Yugoslav wars, my consciousness of history, politics and security – of what can happen, and how it starts, and where it ends – has still been Yugosplained. Jelena, Aida and Srđan warn in their concluding essay, as our mood seemed to when we sat together:

Yugoslavia also carries a message for our friends and colleagues in the countries we now find ourselves in – believe in your exceptionalism – at your own peril; ignore your past – at your own peril; do not listen to Others amongst you – at your own peril.

My thoughts sit there too. And that sits in my bones.